Before 2013 ends, the Code Switch team pauses to remember some remarkable individuals who passed away this year, and whose stories you might not have heard. This is the second installment; you can see Part I here.

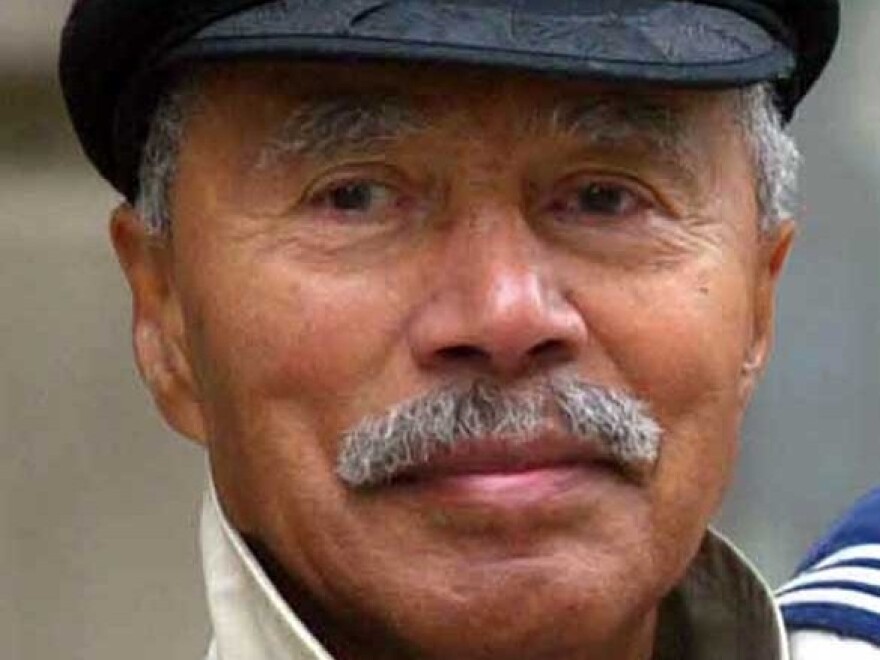

Raul Martinez, Sr.

In the '70s, in Southern California, tacos had hard shells filled with ground beef and were topped with bright orange grated cheese. But Raul Martinez, Sr., knew the Mexican immigrant population living in East Los Angeles craved tacos from back home (soft corn tortillas piled with grilled beef or pork and spicey home-made salsa). So the immigrant entrepreneur took to the streets and started selling tacos from a converted ice cream truck outside bars and clubs in East L.A.

"People thought he was crazy. His own family thought he was crazy," says Gustavo Arellano, author of Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America. But it took less than a year for Martinez Sr. to open his first brick-and-mortar King Taco in 1974 and, today, there are 20 King Taco taquerias in Southern California. Some locations are so busy there's a restaurant and taco truck on the same property handling orders for tacos, burritos and sopes (super thick corn tortilla usually topped with meat, veggies and salsa). And King Taco is now an obligatory photo-op for visiting politicians in their efforts to ingratiate themselves with Southern California's Latino voters.

Legend has it, Martinez, Sr., was the very first entrepreneur to start a taco truck in L.A., something Arellano backs up. A big deal, considering the Southern California taco truck revolution has been credited with sparking today's national gourmet food truck movement. So you can thank Martinez, Sr., not only for your favorite taco truck, but that fancy grilled cheese truck, and award-winning Thai street-food truck you love so much.

Mexican-Americans in their 30s who grew up in Southern California thank Martinez, Sr., for childhood memories of family trips to King Taco, "to eat real tacos, not hard shelled heresies," says Arellano. That was back in the early 80s, he said, when it was hard to find a restaurant that sold a good taco. He admits, now, that's not an issue and there are better tacos to be had elsewhere. But Arellano says you can't discount the pull of nostalgia; his family still travels 35 minutes to the nearest King Taco even though there are plenty of taquerias in Orange County.

Amidst all the success, Raul Martinez Sr. was known as a community philanthropist, raising money for local charities in East Los Angeles. He died on December 3, 2013, in Mexico City, 8 months before his King Taco chain is set to celebrate its 40th birthday.

— Shereen Marisol Meraji

Kim-An Lieberman

She was a woman whose words leapt from the page. Kim-An Lieberman's work reflected her roots with a preciseness found in all of her writing.

Lieberman, who died at 39 in December after a hard-fought battle with gastric cancer, was making waves in Seattle's poetry scene. Her first book, Breaking The Map, played on her Vietnamese and Jewish heritage with tug-of-war themes of mixed identities, borders and displacement.

Lieberman, who was fluent in Vietnamese, French and English, grew up in Seattle and earned a Ph.D. in English at the University of California—Berkeley with an emphasis on Vietnamese literature. Her background might explain her affinity for writing about her culture: Her mother taught Vietnamese at the University of Washington, where Kim-An went for her undergraduate degree, and her father was a professor who researched ethnomusicology. Kim-An herself went on to teach English at the Lakeside School, a Seattle-area high school.

"She had this inner strength that drew people to her but also fueled her to make a big difference," says Kim-An's husband, Matt Williams. Kim-An's work has been published in literary journals such as Poetry Northwest, The Threepenny Review and others. She was shortlisted for a Stranger Genius Award, and was tapped to participate in the Jack Straw writers program.

"[One] thing that struck me about her [work] was the ground she covered in her poems: Her Vietnamese ancestry, the gaps or splits that one experiences as a result of geographic or cultural displacement, or the fact of being mixed-race," says Donna Miscolta, a Seattle-area writer.

Miscolta says poetry helped Lieberman to make sense of her thoughts: "[Kim-An] talked about how it was important for her to be challenged by things she could not always or readily understand; poetry did that, she said."

The want for understanding also propelled Lieberman to explore her own illness in her forthcoming book, In Orbit.

"These poems are about immigration and exile and about cancer – how these events, both of them together – have made her the woman she's become and was becoming," says Terry Martin, the editor who helped publish both of Lieberman's books.

"Poetry — poesis. Etymologically it's from the Greek [phrase] 'to make.' So the poet is a maker. To me, there's something in the fact that Kim-An was involved in making something from this challenge and crisis, right up to her death," Martin says.

Inheritance

My grandmother's older sister, as the story goes,

had only one pencil, precious burden of the only girl

given school while others ran goods to Đồng Xuân market

or scrubbed pots and swept floors for an honest day's wages.

She shaved it by lamplight to a sleek black point,

copied Verlaine verse by verse in perfect tight-packed script.

Here I would protest, surely more than a single pencil

all those studious nights, but my grandmother would repeat

just one, worn to the nub, we have no money for more.

If she lost it, school would have been finished,

lucky she held tight. She wrote out the family's hope,

mastering French and leaving Vietnam, carrying the rest along.

My grandmother, who signed her name in self-taught cursive,

stood watch through my algebra, geometry, calculus years

now collapsed into one kitchen-table moment

with blue-ruled notebook, deducing where x meets y.

Surely highlighters, click-down erasers, infinite pencils,

but I remember only the sitting, the careful numbers aligned.

— Kat Chow

Cecilia Preciado Burciaga

Cecilia Preciado Burciaga opened doors into higher education that had been closed to Latino and Chicano Americans.

As one of the first top Latina administrators at Stanford University, Burciaga never stopped thinking about "the ones not there,"she said in an interview with The Christian Science Monitor. And the ones not there were Latinos and Chicanos, who prior to the 1970s made up a disproportionately small number of students in higher education. When she started at Stanford in 1974, just 2 percent of the student body was Mexican American; Burciaga was just one of a handful of Chicanos on staff, according to Notable Hispanic American Women.

The world of higher education was not kind to minorities, who were viewed as "intruders," says Concepcion Valadez, a professor of education at the University of California Los Angeles. She and Burciaga met when Valadez was a graduate student at Stanford, one of just six or seven Chicanos in the Ph.D. program at the time.

In the midst of the civil rights fights of the 1970s, Valadez says she and her fellow Latino and Chicano students struggled with balancing their political activity with their roles as graduate students. "The biggest fear which all of us felt was that the university was going to sap our political consciousness," she says. "Within our own little group, we were all struggling with how to keep our identity" in a new, often unfriendly environment.

But Burciaga was an example of what Valadez and students like her could be—a respected insider, capable of working within the system without compromising her Chicano pride.

Over the course of her twenty-plus-year career in higher education, which included a position on the White House Commission on the Education of Hispanic Americans under President Clinton, Burciaga worked tirelessly to recruit more women and minority students and staff. She advocated for educational opportunities for minorities, and was a welcoming, beloved mentor to hundreds of Chicano and Latino students, many of whom were the first in their families to attend college.

With her husband, artist and poet Tony, Burciaga lived for ten years as a resident fellow in Stanford's Casa Zapata, a residence hall founded in 1972 for Chicano and Latino students. The couple stressed the "notion of familia," said fellow Stanford alum and Zapata resident Judy Baca, speaking about Burciaga following her death in March.

By the time Burciaga's position at Stanford was eliminated, twenty years after she joined the university, Mexican Americans made up 11 percent of students, thanks in no small part to her advocacy on-campus and as a national figure in the civil rights movement. And today, her legacy continues to influence new generations.

"We take our learnings and we share them and we add to them and our students add to them," says Valadez. Burciaga "was a godmother to a lot of other graduate students who came behind us. We profited from her."

— Nadya Faulx

Richard Street and Otis 'Damon' Harris

It was 1971, ten years after The Temptations had signed with Motown. The group had reached a perilous moment. A string of number-one hits from 1964 to 1968 kept them near the height of their fame, but as the group's popularity grew, so did its internal troubles.

The musical landscape had shifted since the group's early days. 1971 was the year that brought us the "Theme from Shaft," and the funky sounds of Isaac Hayes, James Brown and Sly & The Family Stone were starting to make honeyed ballads like 1965's "My Girl" seem old-fashioned. As Berry Gordy shifted the group's sound towards funkier fare like "Ain't Too Proud To Beg," the Temptations lost one of its charismatic lead vocalists, founding member Eddie Kendricks, who decided to break off on his own over conflicts with the group's direction.

Meanwhile, the rock-star life had taken its toll on the group, which had already parted ways with lead vocalist David Ruffin after his cocaine usage made him increasingly unreliable. Soon, the alcohol-related health issues of Paul Williams — another founding member of the group — had become so significant that he too was asked to leave.

So in 1971, the group had to simultaneously evolve its sound while dealing with the departure of two founding members. They brought on board two singers — Richard Street and Otis "Damon" Harris — to replace Kendricks and Williams.

Street was a known commodity. He'd been subbing in for Williams on gigs since 1968. They found Harris during an audition at Washington's infamous Watergate Hotel, where he beat out 300 other hopefuls to become Kendricks' replacement. At 23, Harris was quite a bit younger than the other group members. Given the short half-lives of boy bands, Harris' youth was an advantage: profiles of the group at this time refer to him as "the sex symbol." But it was an open question whether this lineup of singers could ever reach the heights of the original group again.

That question was answered in 1972 with a song called "Papa Was A Rollin' Stone." The song had originally appeared as a relatively mellow three-and-a-half-minute cut by a group called "The Undisputed Truth," reaching only 63 on the pop charts. But the Temptations version was another animal entirely. After three minutes of pure, vintage, instrumental funk, the vocals kick in and showcase the talents of each of the singers — Melvin Franklin's seismic basso profondo, Street's satin-smooth crooning, Harris' pretty-boy falsetto.

We know the rest of this story. "Papa" became a number-one Billboard hit, won three Grammy Awards and was listed among Rolling Stone's greatest songs of all time.

Only three years after the success of "Papa," Damon Harris had left The Temptations. And the group never had another number-one hit. The Temptations still perform today, with one founding member — Otis Williams — still gracing the stage. Damon Harris and Richard Street both passed away this year, days apart. But unlike the subject of their most famous song, Street, Harris and the other Temptations of 1972 didn't just leave us alone. They left us a masterpiece:

— Matt Thompson

Hans Massaquoi

Hans Massaquoi thought of himself as a typical boy in 1930s Germany. He read about Siegfried, the legendary knight from the same folklore that informed the Nazis' racial mythologies. And like his classmates, he considered becoming a member of the Hitler Youth, who could be seen marching through the streets of Hamburg.

"Barely seven, I, of all people, became an unabashed proponent of the Nazis simply because they put on the best shows with the best-looking uniforms, best-sounding marching bands, and best-drilled marching columns, all of which appealed to my budding sense of masculinity," he wrote in his autobiography, Destined to Witness.

Massaquoi, who died in Florida last January at the age of 87, lived a surreal existence in Nazi Germany. His mother was German and his father was Liberian, making him one of a tiny number of black people who lived under Hitler's regime.

Like his classmates, he'd soaked up all of Hitler's propaganda. But as his schoolteachers rounded up new recruits for the Hitler Youth, they let him know that he could not join. He was shocked. The distraught Massaquoi went home and pleaded with his mother take him to sign up directly at a local Hitler Youth office.

He was rebuffed again, this time more pointedly.

"Since it hasn't occurred to you by now, I have to tell you that there is no place in this organization for your son or in the Germany we are about to build. Heil Hitler!" a Hitler Youth official spat at them.

That rejection signaled the beginning of his slow, painful distancing from Nazi propaganda.

"After each psychologically crushing blow dealt me by one of Hitler's minions, I rationalized that I had been victimized by an overzealous Nazi underling who had overstepped his authority and perverted the Furher's grand scheme," Massaquoi wrote. "I simply could not get myself to blame the architect of the racist policies themselves."

Along with his mother, who raised him while his father remained in Africa, he was subjected to the privations of the Nazi government. Some teachers and neighbors seemed not to care that Massaquoi was black, but that changed as the Nazis tightened their grip on German life. And even though he was harassed and threatened, he was treated differently than the Jews his family knew, like his doctor who were increasingly discussed in hushed tones. Those people simply disappeared.

He became a laborer and a swingboy, one of the dandy-ish teenagers who snuck out and listened to jazz — which was banned by the government for being Negermusik.

When the war turned and the bombs started falling on Hamburg Massaquoi and his mother fled to a rural region where, unbeknownst to them, they lived in the shadow of a concentration camp.

When the war ended with Germany's defeat, Massaquoi headed to Liberia to be with his father's family, before coming to the United States. He joined the Army, and spent most of his military career in the segregated South. He became a journalist and covered the civil rights movement for Ebony, that long-lived bible of black American middle class life, before becoming its managing editor.

"Even at its worse, the American version of racism seemed much more endurable than the Nazism I had already experienced," Massaquoi told the AP in 2000. "In Germany, I was isolated — I was the only one."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.