You think 21st century foodies will go to great lengths for a culinary thrill? (Lion meat, anyone?) Turns out, they've got nothing on 18th century English royals.

Frogs, puffins, boar's head and larks and other songbirds were all fair game for the dinner table of England's King George II, judging by a chronicle of daily meals served to his majesty and his wife, Queen Caroline.

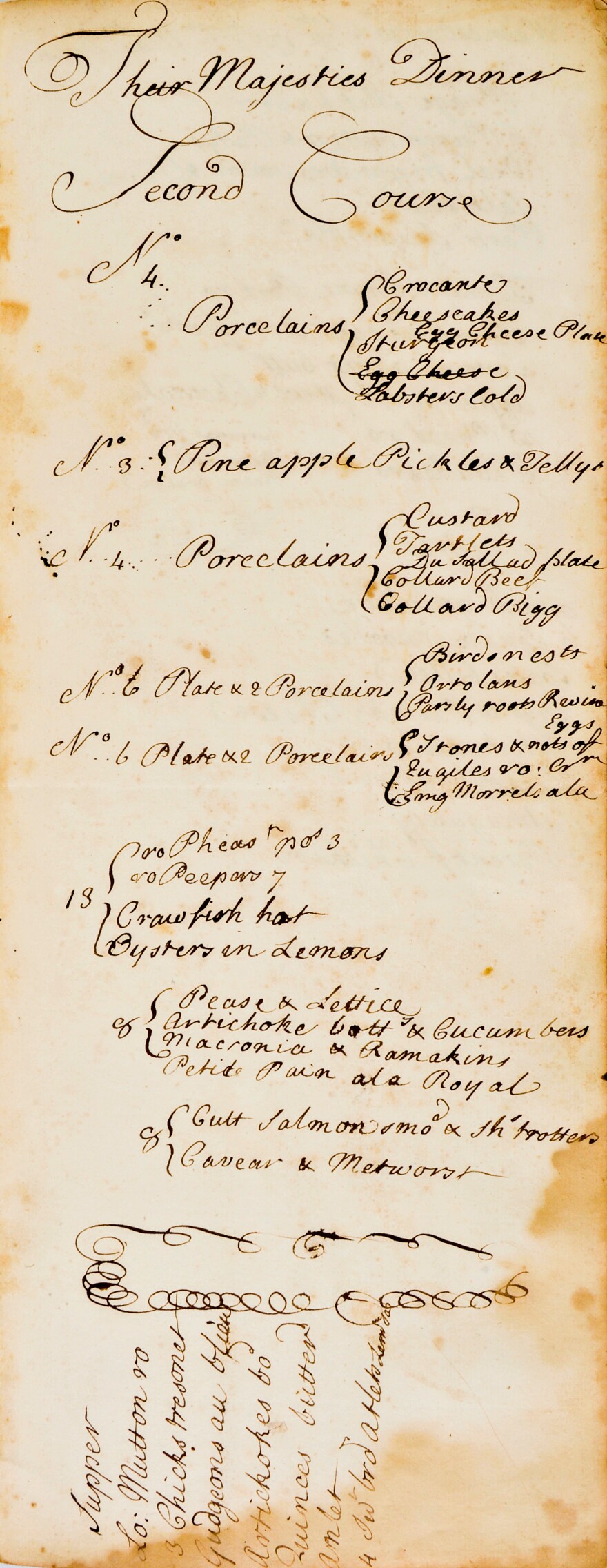

The 160-page, grease-stained collection of royal menus, which details the meals served at Kensington Palace between 1736 and 1737, is up for auction Wednesday. And it contains plenty that might offend our modern, squeamish sensibilities — starting with the royal obsession with eating baby animals, especially songbirds.

They "loved to eat young birds and animals," says Ivan Day, a British food scholar who has examined the rare manuscript. "And by young, I literally mean 1- or 2-day-old babies."

Why? "Because the meat was very tender."

Sounds bad, but as Day notes, it's not that different, really, from eating lamb.

And while it may make bird-watchers blanch, the royal household wasn't alone in its love of the ortolan, a thumb-sized songbird that was a frequent — if silent — guest at George II's table. Indeed, the bird's modern-day endangered status didn't stop former French President Francois Mitterrand from ordering up a dish of ortolans — drowned in Armagnac, no less! — as his last, very illegal meal.

Some of the exotica on the menu was just a case of showing off among the nobility. Then as now, food was status: The rarer the dish, the richer the host serving it. Indeed, one reason why Master Cook William Daniel kept such detailed records, says Day, was simply "a matter of pride."

But in some cases, strange-sounding dishes, like boar's head, were really just a case of the era's nose-to-tail ethos, says Day, who frequently consults with British museums to re-create historic foods.

Diners back then "didn't waste anything," Day says. "They ate everything."

And the menu book isn't just a royal-groupie's window into the extreme eating habits of the monarchy. It's also a reflection of broader cultural, political and technological changes afoot at the time, historians say.

"It's an important little book," says Day.

Take all the tarts and puddings that get mentioned — a sure sign that England's love of sugar was on the rise. The British had waged bloody battles with the Dutch in the previous century for control of the West Indies sugar trade, so the sweet stuff was becoming more available and affordable, says food historian Annie Gray, who works as a consultant with the U.K.'s Historic Royal Palaces.

Pineapples also turn up. The tropical fruit were a rare luxury, but thanks to greenhouse technology, which was just taking off in London at the time, it was possible, albeit painstaking, to grow fresh ones locally for those rich enough to afford the treats, Gray says.

Interestingly, tea — that drink that has become synonymous with the English — makes just a single appearance, says Chris Albury of Dominic Winter Auctioneers, which is handling the auction.

But perhaps the biggest revolution was brewing in the kitchen itself. Though it might not be obvious to a modern reader of these royal menus, British cuisine was actually in the process of becoming simpler — and tastier, Gray and Day say. The sweet-and-savory mixes of the previous era, says Gray, gave way to a more butter- and cream-based cuisine.

The result? Late Georgian cooking, says Gray, was "some of the best food we've ever produced in this country."

Auctioneer Chris Albury says his firm hopes the manuscript will fetch between $8,000 and $13,000. That may sound like a lot of dough for a bunch of old menus, but, of course, says Albury, "it's not just about food — it has wider cultural meanings."

UPDATE 12:57 ET: Albury tells us the book of menus sold for 5,000 pounds sterling — or nearly U.S. $8,300. The buyer? The Historic Royal Palaces, which plans to put the manuscript on display at various sites.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.